Sunshine State Solutions: Understanding Florida’s Substance Abuse Programs

Discover Florida substance abuse solutions. Get help, understand treatment, and find support in the Sunshine State.

May 8, 2019

The sun has just come up on an April morning in 2014 at the Palisades of Bethesda apartments. Chef Ashish Alfred and a prostitute have shot up the last of his heroin. Out of cash to buy more, Ashish throws on clothes and heads to his restaurant, 4935 Kitchen Bar, a few blocks away. Moments later, he’s flat on his face on the sidewalk. Feeling nothing, he pulls himself up and continues. A woman stops him and asks if he’s okay. “Sure,” he mumbles. Later, he’ll discover that the fall had broken four of his teeth.

At 4935, he remembers he doesn’t have the keys. His mother, Veena, who bankrolled the restaurant, had taken them one morning after she and restaurant staff walked in on her son and two women in the upstairs catering venue. A night of drinking and the drug Molly had turned into a naked slip-and-slide thanks to upturned restaurant-size jugs of olive oil.

Ashish yanks the locked panic bar door open, loots the safe and stuffs his pockets with cash. He notices blood on the floor and all over his shirt. His chin is split wide open. He stops at a bodega on the way back to his apartment to buy Super Glue, a hack cooks use to close gashes, stop bleeding and keep working.ADVERTISING

At his apartment, the prostitute helps Ashish glue his chin shut. He showers and passes out. When he wakes, she and the cash are gone. A week later, Veena takes her son on a four-hour silent drive to Pennsylvania and drops him off at a 28-day rehabilitation program.

Four-and-a-half years later, Ashish, 33, is sober and owns three restaurants, Duck Duck Goose and George’s Chophouse in Bethesda and a second Duck Duck Goose in Baltimore. In November, he was invited to cook at the illustrious James Beard House in New York City and did, just before Christmas. After having served a five-course meal that included line-caught halibut with scallop mousseline and osetra caviar, he posed for a picture arm in arm with his mother, he in immaculate chef whites, she in a stunning, intricately embroidered beige chiffon sari over a navy-blue velvet blouse. A portrait of icon James Beard hung behind them. For Ashish, a nightmare had become a dream come true.

Why tell his story? “I want for someone to read it and say, ‘I have a friend who needs to read this,’ ” he said. “I’m not an uber-religious person, but if there wasn’t someone looking out for me, I wouldn’t be here right now.”

Drug and alcohol abuse plagues the restaurant business. According to the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health from the Department of Health and Human Services, hospitality and food service workers had the highest rate of substance abuse among all the industries studied, at 16.9 percent. The rate of alcohol abuse was higher only in the mining and construction fields.

The website Chefs with Issues and programs such as Ben’s Friends and Restaurant Recovery provide safe spaces for people in the industry to deal with issues that probably have roots in the past.

As with many addicts, Ashish’s journey began before he was born. His mother, a Seventh-day Adventist, was a professor in Pune, India. Rather than remain silent in an abusive marriage, she got divorced, taboo in India. She also began a courtship with Rajish Alfred, a student and her third cousin.

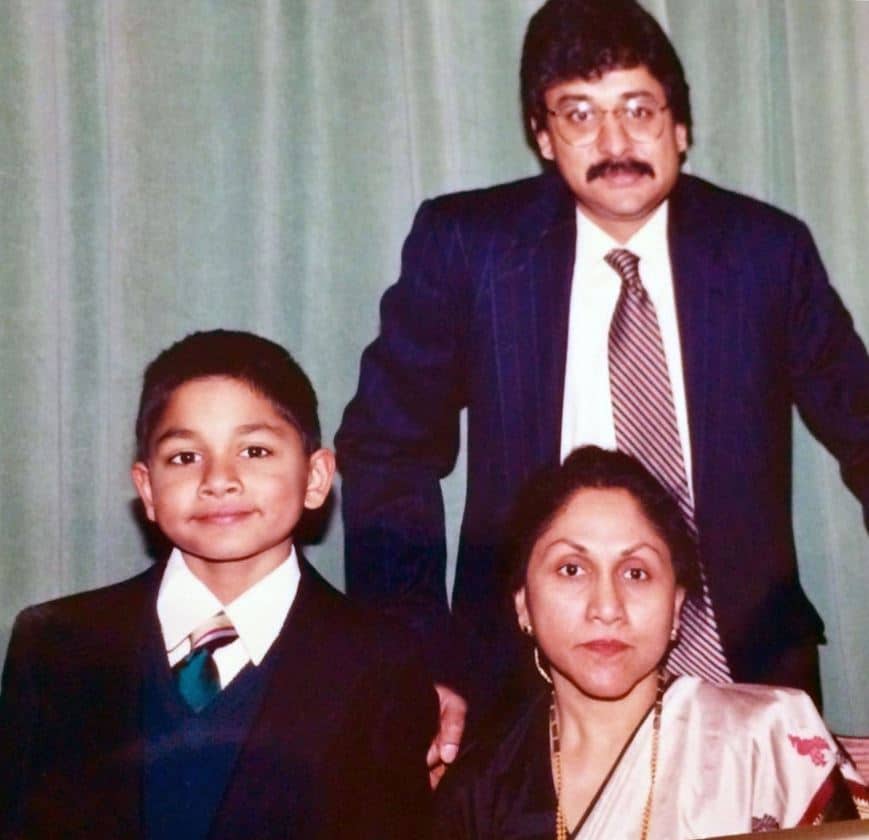

“My brothers told me very clearly that we do not have divorces in our family,” says Veena. “What choice did I have? I came to America.” She settled in Silver Spring in 1982, staying with an American woman she knew from India. She had six suitcases, including bedsheets and a rug, $1,600 (the maximum the United States allowed) and two boys, Shane 12, and George, 6, to raise. Rajish planned to follow once he could get a visa.

An immigration lawyer took $800 to apply for her H1 visa. Six months later, she received a letter saying her visitor visa had expired. The lawyer had never filed her papers. Rather than return to India and now with expired documents, she took a job with the lawyer — and a second job at a senior care facility.

Rajish arrived in 1984 and held a string of jobs, while keeping his drinking binges under wraps; unbeknown to Veena, he had become a severe alcoholic. They married and bought a condominium in 1985. Ashish was born in 1986.

And so his troubles began.

In 1989, Rajish had three DUIs, including one totaling the car, with George inside. He would leave for long periods, then return unannounced.

“I was loud and violent. [Veena] had a couple of episodes where she had to go into a shelter with the boys. There were lots of apologies, regrets,” Rajish says. “When Ashish was 2 ½ , he came charging into our room and bounced on my chest. I was half asleep, hung over. I grabbed him by his shoulders and pushed him down hard, and his femur shattered.” The injuries put Ashish in a body cast for months. “I haven’t even begun to think about how I can ask forgiveness for this.”

Ashish didn’t know the truth about the incident until his teenage years. “I was told I had fallen down the steps,” he says.

Veena got a green card in 1991 and took in three foster children with disabilities to help raise the money to found what would become a chain of AlfredHouse assisted-living facilities, starting in Rockville. (There are now nine.) In 1995, she bought a house in Derwood. Shane, who also struggled with alcohol, had long moved out; George was in California for college.

“That’s where Ashish grew up, where he saw the worst of his father, where he called 911 on him because he was throwing things at me and abusing me,” Veena said.

School provided no respite. In fourth grade, at Spencerville Adventist Academy in Beltsville, he didn’t fit in and was bullied. He stopped doing homework. In eighth grade, he was buying pot, stealing liquor and drinking all day. He hacked into his teacher’s computer to change a grade and got suspended. In ninth grade, he got kicked out, repeating the grade at the public Magruder High School in Rockville.

“I made friends with some real criminals there,” he says. “That’s when it clicked that the more I drank, the more drugs I did, the more fights I got in, the more popular I was.”

His father was in and out of his life. Veena divorced Rajish in 2001, remarrying him in 2006, and during his binges she would send Ashish to make sure he hadn’t burned his apartment down with a cigarette or passed out and hit his head. “I stopped being a kid while I was still a kid,” Ashish says.

He worked various jobs, including at Starbucks, where he got fired for stealing $50 to buy Ecstasy. By 21, he was a VIP host at a gentleman’s club in Baltimore and arranging for drugs for guests. His booze and cocaine habit ballooned. His mother kicked him out, then so did a girlfriend he stayed with, then the friends who let him couch surf.

“I burned every bridge, owed everyone money and went home with my tail between my legs,” he says.

He spent his days watching Food Network, where he caught the cooking bug. In 2008, he made a lavish Thanksgiving dinner for his mother to persuade her to pay for him to go to the French Culinary Institute in New York. She knew he just wanted to get out of Maryland, and she feared drugs would kill him, but she paid the $40,000-plus tuition plus rent, and let him go.

The day before he was supposed to go to New York and sign an apartment lease, he blew lines of coke until 4 a.m. He took the train up, signed the lease, passed out on the floor of the unfurnished apartment and came back home.

Once at the FCI, he excelled. The program included working for the school’s in-house restaurant, where a samosa-like appetizer he created made it on the lunch menu, an honor. Veena was proud, despite cultural misgivings.

“Nowadays, chefs have great prestige, but if my grandfather saw this, my father, they would weep, because I come from the ruling class in India, where they have their own kitchens and chefs,” she said. “But because my son was happy, I was happy.”

Ashish worked in restaurants around New York, such as DBGB, Lupa Osteria Romana and Bar Pitti. Chefs told him he could go far if he put his demons behind him. Instead, he partied on, sometimes missing work and getting fired. He sold coke. On two trips home to see his parents, he was arrested for DUIs.

He returned to Maryland in 2012, where the 4935 space in Bethesda had become available. Veena sold a property to finance the business. She knew that Ashish was still drinking — he would disappear for days at a time — but not that heroin had entered the picture.

“I liked the idea that I could die from it,” he says. “That seemed like a comfortable death.” The best-case scenario, as he saw it, was that he would get a good buzz; the worst-case, that he wouldn’t wake up. “I didn’t do it to the point where I’d get sick if I didn’t have it. If it wasn’t dope, it was [oxycodone] — whatever I could get my hands on. I was doing so much blow, the oxy would even me out, people said. And it worked.”

It didn’t work.

One day in 2014, Veena gave Ashish an ultimatum.

“I told my son, ‘If you are willing to go into rehab, I am with you. I will pay for it. Otherwise, you will not see me and I’ll have nothing to do with you. Call and let me know by Friday night,’ ” Veena says. “I left my son standing there on Cordell Avenue, miserably thin, injured emotionally and physically, with the fear in my heart that I will not see him again, that he will kill himself.”

Ashish’s father, recently sober and living in Philadelphia, encouraged his son to go.

“Like any good drug addict, I told them to f— off and I’d figure it out on my own,” Ashish recalls. “But that lasted only a few days.”

At the Caron Treatment Center in Wernersville, Pa., counselors asked Ashish to get rid of anything he might have on him. He found some cocaine in his wallet and threw it out. “And that was it,” he said. “I was done. They put me in detox, and I never wanted to go there again. I never wanted to feel that again.”

Ashish calls it the best 28 days of his life. “For me, the most value was in the family part of it. There was a three-day workshop with the parents that really changed my life.” Pent-up thoughts and memories surfaced that made the work valuable even if it was excruciating. He recalled that in Silver Spring when he was very young — 5, 6, 7 years old — various workers and tenants were going through the house, and “they got handsy.” He didn’t mention it to his parents until rehab. “What could they say?” he asked. “It wasn’t their fault. I knew as a child that it was a secret not to be told. I don’t think it went too far. No, not too far.”

Says Rajish: “We shared a lot of things we never talked about. . . . Ashish and I were in it. Our bond was elevated from father and son.” It wasn’t until years later, though, that Rajish fessed up to the violence and asked forgiveness.

“I said, ‘Yes, fine, thank you,’ ” Ashish says, “and kind of kept it moving. And that was the end of it. I mean, I spank my dog and feel terrible. I can only imagine how he must feel.”

When he returned to Maryland after rehab, Ashish lived in a halfway house for two months. On the first night, he was slinging drinks at his restaurant, which remained open while he was gone, because a bartender had called in sick. “What was I going to do? I was short-staffed, and no one wanted to work for me.”

Ashish now attends Alcoholics Anonymous meetings and sees his sponsor once a week. Until a year-and-a-half ago, he submitted to random drug testing four or five times a week to reassure his mother and staff. He told them if they ever thought they had something to worry about, he would happily submit to testing again.

He opened Duck Duck Goose in April 2016 and a Baltimore outpost in June 2018. He bought a house in Baltimore in July and lives there with his dogs, Otis and Marco (after the British chef Marco Pierre White).

There have been challenges. George, his half-brother and surrogate father, died suddenly of a heart attack in 2015. Ashish had George’s birth and death dates tattooed on his right hand, and when he rebranded the struggling 4935 Restaurant in 2017, he paid further tribute by naming it George’s Chophouse.

He recently went to court for a young woman who works for him. She is new to sobriety, and her mother, with whom she lived, had left. The rent hadn’t been paid in three months, and his employee was going to be evicted. Ashish got her an apartment and took money out of her paycheck for rent.

“The judge said, ‘I don’t like the fact that you work in restaurants, because I think that’s a terrible environment for somebody trying to stay sober,’ ” Ashish said. “I don’t necessarily agree with that. I think it’s the environment you create. I think, as a chef and owner, that if I foster an environment where it’s cool to be blowing lines and doing shots at the bar at the end of the night, then, yeah, that’s what’s going to happen there. It’s not acceptable in any of my places. I’ll take them out for a drink after work and buy them one drink and swipe my card and get out of there.”

Ashish sees his mother every Saturday, either for lunch or at the Southern Asian Seventh-day Adventist Church in Silver Spring. He says she has made peace with his career.

“It really took a long time for her to understand and respect what it is that I actually do,” he says. “But I know she’s happy and she’s happy with me and how far I’ve come. I mean, five years ago I was almost . . . dead, and now I’m cooking at the Beard House. That’s a big deal.”

If you or someone you know is struggling with drug or alcohol abuse and in need of addiction treatment in West Palm Beach, give Summer House Detox Center a call at 800-719-1090 to schedule a FREE consultation. You can also visit us at 13550 Memorial Highway Miami, FL 33161. We are open 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

Discover Florida substance abuse solutions. Get help, understand treatment, and find support in the Sunshine State.

Unlock lasting recovery with personalized addiction treatment. Find your custom path to triumph in Florida.

Opioid use disorder explained: symptoms, crisis stats, and effective treatments. Start your recovery journey in Miami, FL.

For immediate assistance, please call our Admissions Specialists at 800-719-1090.

Speak With A Qualified Addiction Specialist 24/7